Rewriting Newton’s Zoning: Can it be Contextual and Aspirational?

/By Michael A. Wang

The City of Newton, Massachusetts is going through an extensive process to rewrite its Zoning Ordinance. This is a major undertaking for a City in which 85%-95% of the parcels have a non-conforming aspect. That may seem like a surprisingly large percentage, but many long-established communities have considerable building stock that pre-date their current bylaws. In Newton, nearly three-quarters of the City was built before the establishment of the 1953 Zoning Ordinance. Many see zoning as an impediment to forward-thinking development, while others believe that it is a helpful tool for preserving the unique qualities of a place. Perhaps it is not so black and white.

One of the challenges for any city attempting a comprehensive rewrite of its zoning is to convince its constituency that the new ordinance will ensure that future development will be contextual. Outspoken community members know what they don’t like and often default to a NIMBY platform. As such, it is a smart approach for a city to say that new regulations governing both residential and village contexts will increase the likelihood that new development will complement the scale and spirit of the existing context. However, it is also important to consider the aspirational side of the equation.

Building consensus through contextual design

In a recent two-part forum for architects and designers held by the Newton Planning and Development Department and facilitated by Form + Place, a Newton-based architecture and planning firm, participants explored the ramifications of proposed site and building design dimensional criteria. In introductory remarks, the City reiterated one of its guiding principles, that what matters is a building’s relationship to its neighborhood, not to its lot. This underscores Newton’s desire to move away from Floor Area Ratio [F.A.R. dictates that the square footage of a building be directly proportional to the size of the lot on which it is being developed] as a key determining factor for what one can build on a specific parcel. One of the biggest issues that the City is trying to address with this approach is to prevent developers from purchasing oversized lots or assembling contiguous parcels in order to build “monster” houses or commercial buildings that are not appropriately-scaled for their immediate context. While it is easy for community members to say that a building is too tall or that having a drive-through in a village context ruins the feeling of a well-defined shopping street, the question of how prescriptive a zoning bylaw should be with respect to building and site design criteria remains a source of much debate.

The Newton Centre “triangle”

During the forum, designers looked at a range of sites, including a couple of key parcels in Newton Centre. While the reuse of the City-owned triangle [parking lot] at the core of Newton Centre has often been the focus of redevelopment speculation, participants explored the surrounding blocks, asking questions such as whether one-story retail blocks are adequate to define a village center with significant open space, and how does one find the right balance between the pedestrian and the automobile in a location where there is multi-modal transit access.

What is the appropriate balance of development and open space?

The question remains, how aspirational should a zoning bylaw be? Rewriting a regulation so that a great deal more of a community’s existing buildings and sites are conforming is a good starting point but, when a developer with significant land holdings puts forward a vision that will impact a substantial part of a city, there must be additional mechanisms available to define an approvals process that is adequate to vet the design. The City of Newton currently has numerous large-scale projects in the works, including along the Washington Street corridor, at the Riverside Station and on the Newton-Needham line. While projects of this scale need to be addressed on an individual basis through specific mechanisms that are outside of an overall zoning regulation rewrite, they should be considered holistically by a community.

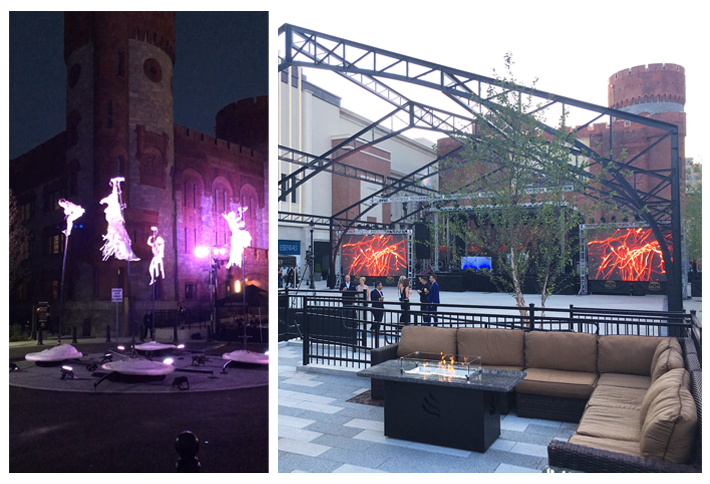

In Watertown, Form + Place recently helped write a new Regional Mixed-Use District for industrial lands along Arsenal Street to help facilitate the development of Arsenal Yards. This project came to fruition because the Town had a Comprehensive Plan in place that outlined aspirations for the redevelopment of this area, and a development team – Boylston Properties and The Wilder Companies – came forward and was willing to work with the Town to help execute a shared vision.

Reshaping Watertown’s Arsenal Street Corridor

The Newton community should be open to a similar process and should position itself to take advantage of the visionary opportunities that public–private partnerships can bring. Whether defining new overlay districts or utilizing a master plan special permit approach, there are many mechanisms available to allow for adequate oversight through a well-defined approvals process. Most of the large-scale development currently happening is proposed along major commercial corridors but residents of village centers such as Newtonville and West Newton are certainly feeling change.

The challenge for a community such as Newton is to be proactive and aspirational. There are many successful models for Smart Growth that are currently being implemented in similar communities throughout the northeast. So, instead of being fearful of large-scale development, stakeholders should ask themselves how they can help shape proposed development so that it can be both contextual and forward-thinking.