Rebuilding Trust: Public Space as Common Ground

/By Aidan Coleman

The pandemic has drastically altered society by restricting gatherings, resulting in people flocking to the internet and socializing behind screens. While technology has risen to the occasion to help fill the social void, there’s no question that this widespread shift to online communication has been disruptive and has forced people to adjust. In addition to the mental stresses of the pandemic, civil rights issues and politics have caused a general fear and distrust of those who are unfamiliar. In response, beyond the necessary public realm changes for health protocols, designers must work to create public platforms that will foster rebuilding of trusting relationships in our communities.

Public space programmed to allow for active, face-to-face interactions

With the pandemic forcing society to adapt to online communication, we are left largely isolated within our closest social circles. It doesn’t take much experience being online to know that being stuck behind screens all day has negative impacts on our mental health, but there have also been studies on the effects of technology on the human psyche - Dr. Helen Riess is a psychologist who has recently released a book called The Empathy Effect, which describes how the increased communication through text on the internet can damage our ability to feel empathy due to the fact that we can’t see facial gestures or voice tones that should go with our words (Street Roots). It’s no surprise that our dependence on the internet and social media has led to countless misunderstandings that often lead to hostility. The way we, as designers, can catalyze face-to-face interactions is with architecture and programming. Andreea Cutieru describes from her ArchDaily article:

“Social capital refers to the relationships established between social groups in heterogeneous societies, through shared values, trust and reciprocity. Substantial social capital means increased cooperation among citizens, less friction and a keen awareness of the common grounds and entwined fates. Architecture can help build social capital, and numerous design strategies can generate fertile ground for social interaction and various unplanned activities.” (The Architecture of Social Interaction)

While we can’t force people to interact, architecture, with proper programming of the spaces, can provide attractive gathering places that allow people to participate in shared experiences with one another, ultimately encouraging healthy communication.

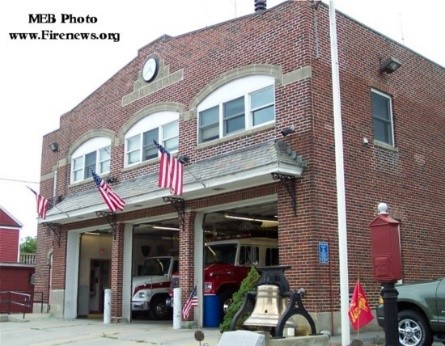

Studio Gang is an architecture firm that explores many projects and ideas that intertwine architecture and planning with building relationships within a community. They released a booklet in 2016 called Civic Commons that discusses methods for cities to activate their common spaces, and it’s apparent that we need this type of urban planning and design more than ever in 2020. The booklet runs through how to evolve seven types of urban gathering spaces (libraries, parks, rec centers, police stations, schools streets and transit stations) by creating open and comfortable spaces for the community to have diverse experiences while they socialize, work, learn, play, or deliberate. To achieve the goal of trusting others in our community and beyond, we must reshape our urban spaces to allow for comfort and diversity in shared experiences as people come together face-to-face.

Civic Commons Master Plan Graphic, by Studio Gang

While evolving civic spaces may seem like a long-term goal that can only be realized after people can gather safely, efforts to transform our environment are already occurring in real time through social distancing. The outdoor realm is being utilized in the practice of tactical urbanism. Pop-up furniture and boundaries reshaped the streets, and in our previous blog on Streetscapes, F+P discussed how easily these temporary street markers could be implemented permanently, allocating more space for pedestrian activity, as opposed to the automobile.

Outdoor dining is a must in our current environment, filling street space with attractive ambiance. Photo by Aidan Coleman

Reorganizing cityscapes for pedestrians is only the first step in evolving our urban spaces to improve public physical and mental health. An important next step in sparking community collaboration and shared experiences is through programming. Even while social distancing, tactical urbanism can be used to block out stage and viewing spaces for performances. When Italy was in lockdown, their viral videos of musicians playing and singing out of their apartment balconies for everyone stuck inside were an uplifting sight. Public art can be a way to bring vibrancy to an otherwise lackluster environment. Vendors can spread out into outdoor pedestrian space to allow for interactive display experiences. Eventually, participation in games/ sports in our larger pedestrian urban environments will literally bring people together. There is even a new movement in urban areas called “guerilla gardening” where individuals take advantage of underutilized spaces and plant varieties of greenery to enliven the area.

Dynamic pedestrian spaces created with multiple layers of design elements. Photo by Aidan Coleman

While we have been able to temporarily reshape urban areas to make public life work with social distancing for physical health purposes, our social and mental health have taken a back seat. This year has made clear that these issues are also of great importance. As we weather this pandemic, we must design for rebuilding community trust, promoting spaces that offer common ground between strangers for a variety of goals and collaborations.

Sources and Inspirations

“Civic Commons.” Studio Gang, studiogang.com/project/civic-commons.

Cutieru, Andreea. “The Architecture of Social Interaction.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 7 Aug. 2020, www.archdaily.com/945172/the-architecture-of-social-interaction.

Green, Emily. “How Technology Is Harming Our Ability to Feel Empathy.” Street Roots, Street Roots, 20 Feb. 2019, www.streetroots.org/news/2019/02/15/how-technology-harming-our-ability-feel-empathy.

“Polis Station.” Studio Gang, studiogang.com/project/polis-station.

Zilliacus, Ariana. “Studio Gang Creates 7 Strategies to Reimagine Civic Spaces As Vibrant Urban Hubs.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 27 Sept. 2016, www.archdaily.com/795905/studio-gang-creates-7-strategies-to-reimagine-civic-spaces-as-vibrant-urban-hubs.