From Initial Concept to Realization: Visioning Tools in the Design Process

/By John Rufo

During these difficult times with election distractions, COVID challenges and complicated economics, developers and municipalities alike are looking to tee up and frame future development opportunities through zoning, visioning, master planning and feasibility studies. Form + Place, a Newton-based architecture and planning firm, has a unique approach to facilitating these efforts through a design process that utilizes sketching and analytical diagraming to, not only help set the direction for a visioning effort but also, provide a roadmap post-visioning that helps keep projects on track.

In a mixed-use master plan process, there are myriad complexities that tend to be overwhelming for anyone outside of the development team to fully comprehend. The vision that is ultimately put forward therefore - say, through a series of key renderings - tends to be the image that people grasp hold of and refer to again and again when assessing the design. Form + Place defines and articulates that vision through an iterative process of sketching multiple plans and vignettes that allows our clients to visualize the place-making and architectural potential in a project. The ideas in these iterations inform the final vision which can then be understood by a local municipality, and its stakeholders, throughout the entitlement process, or selection process in the case of an RFP. These images, in the form of renderings, elevations or illustrative plans, also serve as our road map to tracking the progress of the design post-visioning as the project is realized.

This series of sketches, for example, traces the development of a public space that integrates upper and lower street-level environments. As the final vision moves forward in its development, the ideas of the early iterations act as checks on the final design.

Riverside Station - Newton, MA

On the recently approved Riverside project in Newton, we served as part of the city’s peer review team and authored the city’s design guidelines for the development. Working with the staff, various committees and the developer [Mark Development] through an iterative process, diagramming key urban design objectives such as focal points and view corridors was a critical aspect of breaking down the complex urban qualities of the design into a legible critique and accessible guide for the city council and members of the public. The design guidelines themselves needed to function as both a roadmap for moving the project forward and a template to review the final design for consistency at the building permit stage. In these instances, diagramming is an important tool for communicating design goals and standards during a public process and within the context of a peer review.

Diagramming on precedent images to illustrate key guideline objectives such as storefront continuity and façade scale

Springfield Northeast Downtown District – Springfield, MA

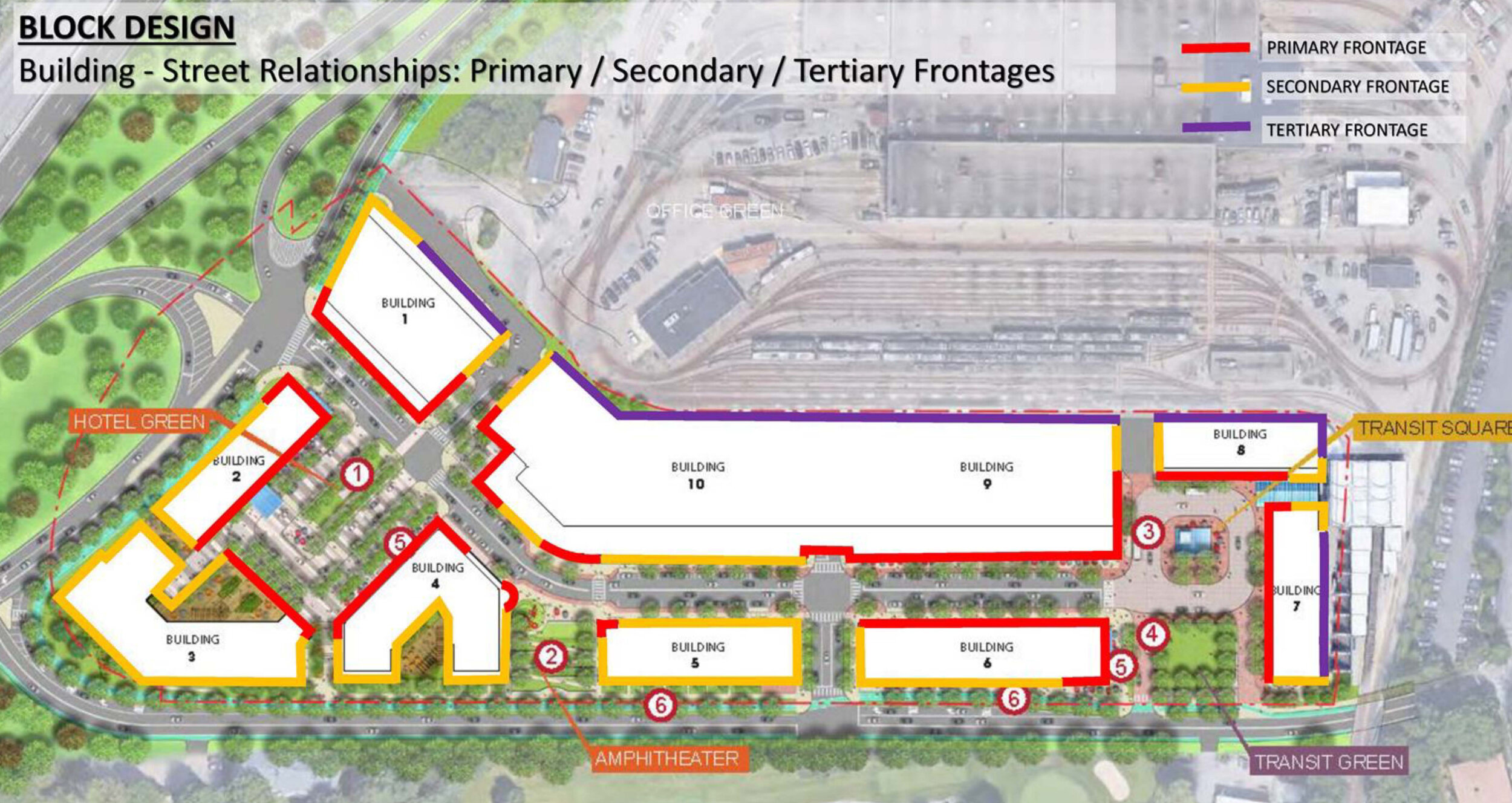

In Springfield Massachusetts, Form + Place has been working with the city to develop a master plan for the Northeast Downtown District to put in place an urban framework that will catalyze future development. In a project area of this scale, the complexities of each street and parcel can easily get in the way of seeing the larger objectives of the effort. Diagramming street and open space hierarchies is critical to developing consensus on the focus of the master plan, which will ultimately leverage public funding to upgrade important corridors, open space, and development sites.

Setting the scope of the study by diagramming the main commercial and transportation spine in relation to surrounding neighborhoods

Focusing on the importance of particular design proposals supporting the larger phased master plan objectives

Identifying a network of key green spaces in the context of the larger city fabric

Moving into the more granular aspects of the exercise, specific public realm assets like the Apremont Triangle were re-imagined through an iterative sketch process that addressed issues of open space, traffic flow, building uses and infill opportunities. These sketches were also used as part of a three-dimensional modeling process that allowed people to visualize the proposed changes and imagine what this critical space might be like in the future.

Exploring the transformation of public space through the integration of unique landscape qualities and scales

Exploring more active design strategies that create a variety of types of spaces

Applying concepts to a 3D model of the space to better understand scale, light, urban edges and vistas

Re-testing the initial concepts in a more fully engineered plan

Sketching and diagramming never really stop in the course of the design process. As buildings and parks and streets begin to take shape on paper, and the scale of the drawings gets larger and conveys more detail, sketching and diagramming the details serves to constantly clarify intent as well as articulate the finer design details. We often use a metric for judging our own design proposals that poses the following questions:

Does the neighborhood or district work when seen in the context of the city?

Does the street work when seen in the context of the neighborhood?

Does the building work when seen in the context of the street?

If we can keep getting to “yes” as we ask these questions throughout the process, then we know we are in good shape. If we arrive at “no”, then we go back to the drawing board.